Chinese

Chinese

Cross-Cultural Influences

For centuries the Chinese porcelain industry had been the envy of Europeans who wanted the prestige and wealth that mastering the secret to porcelain manufacture would bring them, but it wasn’t until the turn of the Eighteenth century that Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus (a German scientist) first developed a form of hard paste porcelain. By the time Tschirnhaus died in 1708, Johann Friedrich Böttger (an alchemist) had already developed the paste into what is now known as Böttgersteinzeug (a red stoneware). He was employed by King Augustus II of Poland and Saxony (1670–1733) who set him up in a laboratory in Albrechtsburg Castle (Meissen) in order to develop the recipe into a commercial paste. The castle was chosen, so that the secret of the paste, once a commercially viable formula was developed, could be closely guarded. The Royal-Polish and Electoral-Saxon Porcelain Manufactury was also established and started manufacturing porcelain in 1710.

The factory at Meissen soon started producing a white bodied clay that was recognisably white porcelain. The earliest pieces were marked AR for Augustus Rex then KPM with Crossed swords (from Augustus’s crest) and then after 1722 the Crossed sword mark without the KPM was used as the main identifying mark to indicate Meissen Manufacture (as it still does).

The designer, Johann Gregorius Höroldt, who stayed with Meissen for 50 years from the early 1720s developed many of the colours and delicate designs that now make early Eighteenth Century Meissen both recognisable and extremely desirable. However, the prime influence for Meissen’s earliest forays into porcelain was the highly sought after Chinese porcelain that had originally sparked the race to make porcelain.

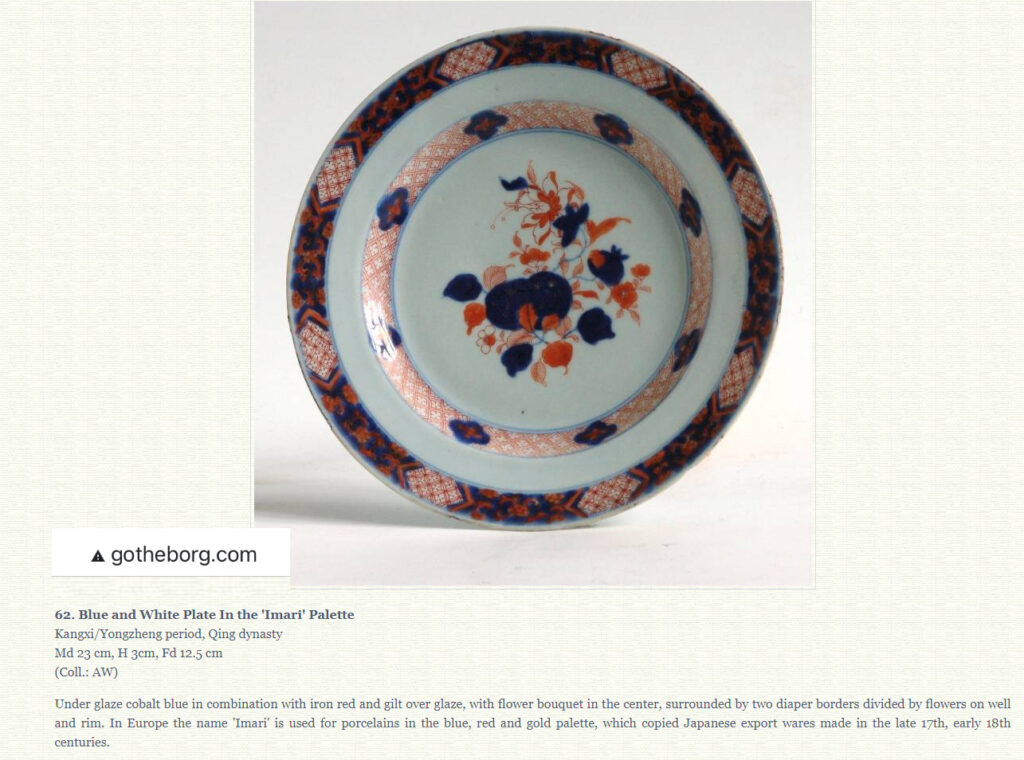

For example, one of the best known patterns that Meissen produced in the early days of the factory was the blue and white onion pattern (Zwiebelmuster) aka as the bulb pattern. It is believed that the decorations that bordered the original Chinese dishes were actually peaches or pomegranates (used on marriage and birthday porcelain as wishes for fertility and longevity) . The “onion/bulb” was a European interpretation of the pattern. (You can see more examples of the pattern by googling Meissen Onion Pattern and there is more info on Höroldt here http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/artists/997/johann-gregor-horoldt-german-1696-1775/ and on the pattern here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Onion)

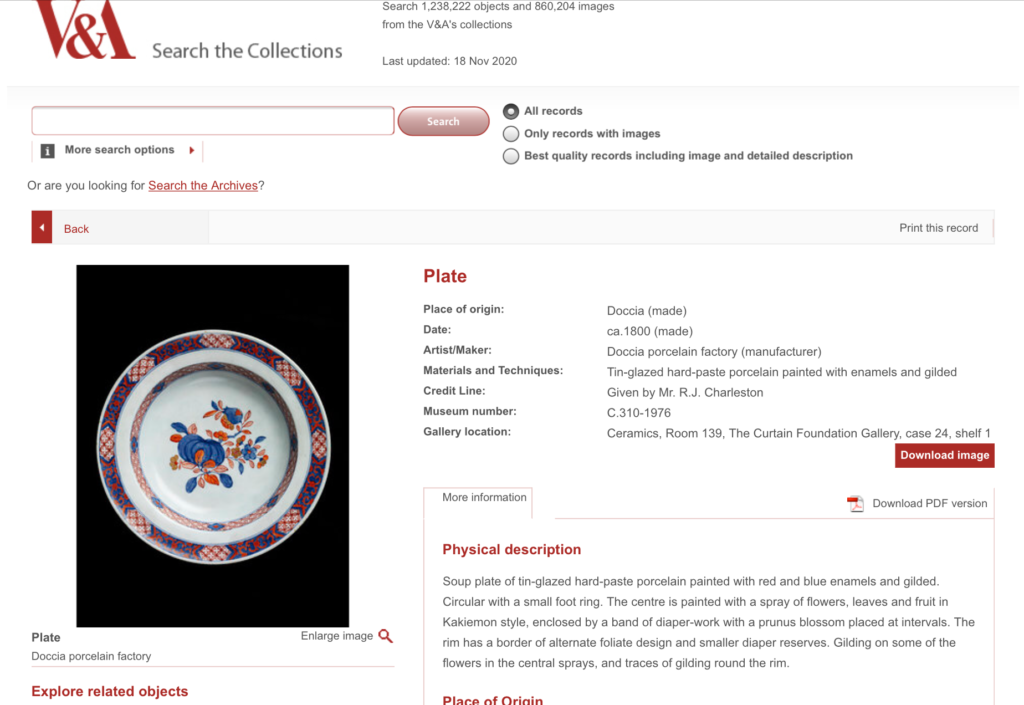

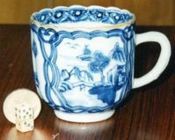

Seeking inspiration from the Chinese originals was not restricted to Blue and white – the rise in popularity of Chinese Imari porcelain (underglaze blue and white with overglaze red – often gilded) also captured a Meissen decorator’s imagination. An example of this cross-cultural exchange is the following piece. The first two illustrations are of an 18th Century Meissen tea bowl in the style of an earlier Chinese Imari piece. It is distinct from the Chinese Imari, with its dark cobalt/ almost black blue underglaze and its 14 spiraling lobes with an added purple pigment that became popular on later more extravagant Meissen pieces.

This small tea bowl uses a pattern style that will be very familiar to collectors of later 18th Century porcelain from the Worcester Factory, although the pattern predates by over 50 years what became known as the “Queen Charlotte” pattern (after a visit to the Worcester factory by George III and his popular wife, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz c.1777).

Not long after this pattern was introduced by Meissen, 18th Century Chinese makers were either commissioned to copy the Meissen pattern or were asked to make replacements for it. This early Eighteenth Century Tea bowl and Saucer copies the Meissen pattern so faithfully, it even mimics the Meissen mark. Although I am sure that there are many others, so far I have only seen three Chinese copies of the Meissen pattern, one is late Eighteenth Century, but the remaining two are earlier and almost identical to the Meissen original – the first was sold at Bonhams in 2017 as a reference piece from the superb Brigitte Britzke Collection (a well-known collector of Meissen) and the other is illustrated below from my own collection.