antique

antique

Dutch Decorated Creamware

Dutch Decorated (Flight into Egypt) Jesus Mary and Joseph Creamware plate

For over a hundred years European countries sought for ways to create a fine hard paste that could compete on an equal footing with the popular porcelain pouring in from China via the Tea Clippers and Dutch Trading Ships. The problem, in the UK, was that the key ingredient was Kaolin that gave whiteness to the finished pottery and elasticity to the wet clay making it more malleable and finer that earthenware – although by modern standards Kaolin, on its own, lacks plasticity . Very few natural deposits had been found until the middle of the eighteenth Century, when William Cookworthy found deposits of Moor stone and Growan Clay in Cornwall.

Cookworthy immediately started to experiment from his Plymouth based pottery and by 1768 he had patented a formula that mixed the Growan Clay with other more traditional clay mixes and another new ingredient commonly called China stone or Petuntse (a feldspathic rock) that gave the fired clay translucency. Plymouth was, therefore, the first producer of what we now call British hard paste porcelain, inherited in turn by Bristol and then Worcester.

The patent, however, left other potteries now competing with white Plymouth porcelain in addition to Chinese porcelain and Dutch tin glazed delft ware. Even though Kaolin was discovered in Staffordshire they were forced to develop their own pastes and formulae from their own local clays, until a collaborative group of potters bought Cookworthy’s patent in the late eighteenth century.

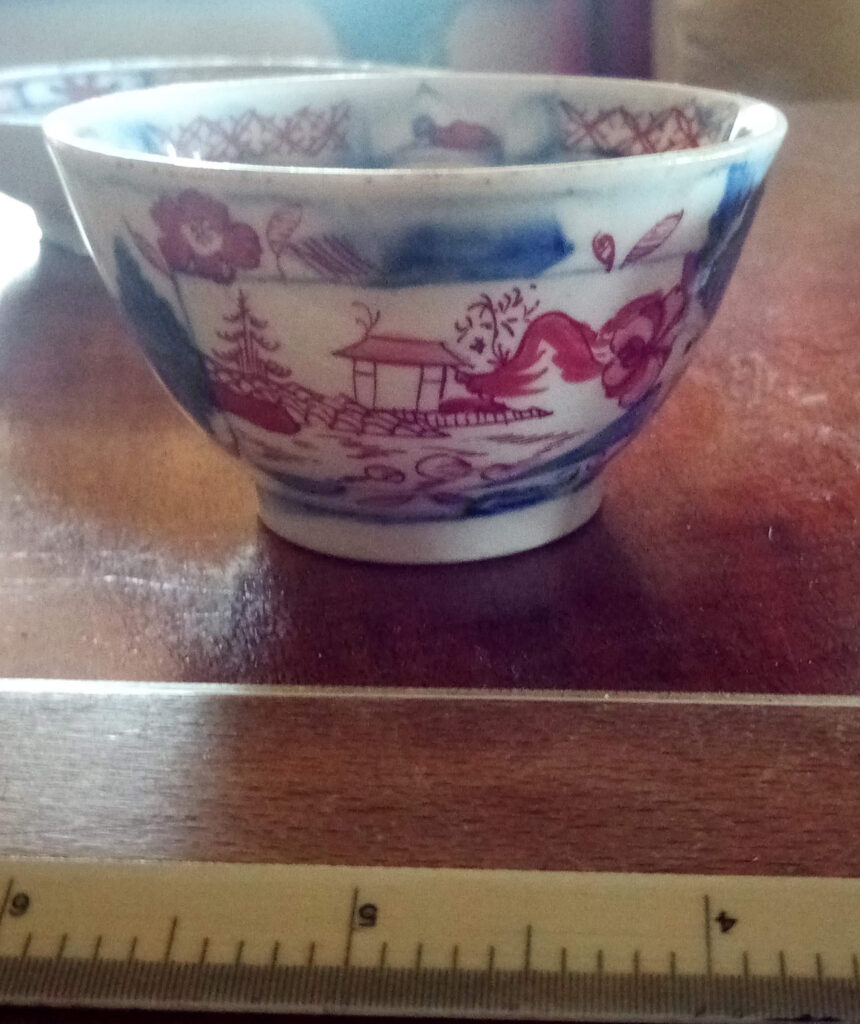

One of the most distinctive of these interim pastes we know as Creamware. Made with finely powdered clay, it was more malleable, smoother and easier to work on than Delft clay that was powdery and brittle and easily broken (relying to an extent on the strength given to it by its tin glaze). The more delicate and creamy warmth of the fired clay coming from potteries like Leeds lent itself to the bold colours favoured by Dutch decorators. Strong, but very light next to Delft, Creamware was exported in quantity as blanks to be decorated in Holland and Dutch decorators came to the UK to work in the potteries. Leeds is particularly notable for its success in this field and its wares were extremely popular in Holland.